I recently purchased some Ya Shi Xiang oolong from Zerama Tea, figuring I should try some Dan Cong as I haven’t had any. I really love the oolongs that I typically drink and haven’t strayed much past them, but it was time to sample something new. Even a characteristically dry scientific article noted that Phoenix Dan Cong “is one of the most tasty and fragrant varieties of tea in China” (Zhang et al. 2018). (The study also supports Dan Cong’s antioxidant and possibly anticancer properties so this tea is a win-win.)

The tea

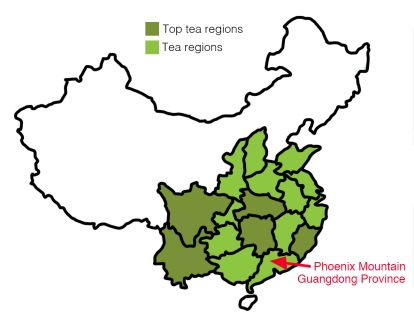

This oolong is produced near Phoenix Mountain in China’s Guangdong Province, with Dan Cong meaning “single bush.” Each variety of tea plant has its unique aroma, and some of the plants are hundreds of years old.

Ya Shi Xiang’s more colorful name is Duck Shit—apparently inspired by the region’s yellow-brown soil—although the tea leaves have an incredibly strong honey and fruit aroma!

Like other oolongs, Dan Cong boasts large, intact leaves. This Ya Shi Xiang’s dark green leaves have been tightly rolled lengthwise.

And I discovered that this is a tea that really changes depending on what it’s brewed in and even what teacup is used. Paula, owner of Zerama Tea, had asked me what I thought of this oolong, and I have to apologize that my response is a bit convoluted!

For pretty much every tea I drink, I decide pretty quickly whether I like it or not. This Ya Shi Xiang, however, was different.

At first, I didn’t wildly like or dislike this tea. I wasn’t actually sure what I thought except that it sent me into a different direction, one experimenting with brewing in different vessels—because although the aroma of the dry leaves is an intoxicating honey-apricot, getting that flavor was at first elusive.

Brewed in clay shiboridashi from Japan

On day one, my family brewed the leaves in a Japanese clay shiboridashi, beginning with a 10-second brew, using about 3 grams of leaves to 75 ml of water at 190°F.

The aroma was sweet earth, soft and pleasing, and, to me at least, with a hint of dark chocolate. The liquor, however, was more intense than the aroma, bold, with a lingering astringency (or bitterness, according to our sugar-loving son-in-law).

While the next infusion was less astringent, this tea has no sweetness to it at all. We struggled to describe it, and agreed that there were other oolongs that we preferred, although we didn’t dislike this tea.

Brewed in gray clay teapot from China

Unsatisfied with this experience, the next day I brewed the leaves in a Chinese Yixing (gray clay) teapot, using about 3 g of leaves to 60 ml of water, at 190°F, and began with 10-second infusions.

As resounding proof that brewing parameters can make a world of difference, this was a different tea!

I got the same straw, a bit of toastiness, and vegetal that the shiboridashi yielded, without much sweetness, along with perhaps roasted vegetable, but this time the tea had an incredibly satisfying smooth, buttery mouthfeel and a pleasant aftertaste. Using a Jian Zhan teacup, the tea was even more mellow and smooth.

Subsequent infusions changed from one to another, some with more vegetal, another more toasty, but that buttery smoothness remained. Eventually a sharper note began to predominate, and then a bit of bitterness. The tightly rolled leaves didn’t unfurl much at all.

We don’t often think of our cups or mugs as reacting with its contents, but outside porcelain and glass, there is a reaction. When the material is porous, the liquid’s flavor and even aroma may be partly absorbed into the cup rather than being fully released.

This can either ruin or improve a tea. You might lose bright notes that you want to retain, but conversely, the tea may be softened or more desirable notes heightened.

In the case of Jian ware (or Japanese tenmoku or temmoku), as I touched on in an earlier post (Why You Should Choose Your Teacup Carefully), the iron content of the cup reacts with the tea, and in fact, it’s the iron oxide that accounts for this ware’s gorgeous design.

Iron oxide precipitates when the piece is fired in the kiln, forming the crystalline markings and iridescence that characterize these pieces. For an “oil spot” effect, the potter can get the glaze to form drops by manipulating how quickly the kiln cools (Beurdeley and Beurdeley 1974:138).

This iron content also works to “improve the alkalinity” of the tea, according to Teavivre—but of course that depends on the specific tea and whether you want that change or not.

Likewise, brewing in a clay teapot means that the tea and clay interact with each other. In the case of this particular oolong, I did not care for the end result when brewed in my shiboridashi, but I did enjoy it when brewed in my Chinese clay pot.

Brewed in glass

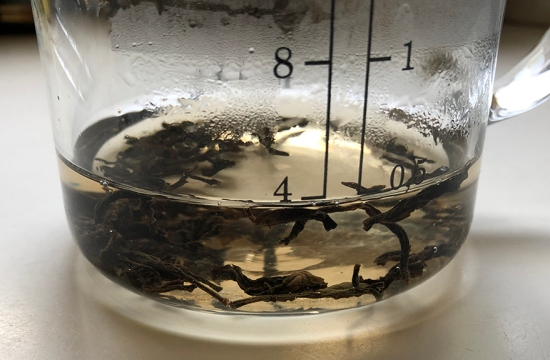

Just to verify I was tasting a real difference, I then brewed the tea in a glass beaker, western style for 3 minutes at 190°, glass being a truly inert substance.

That slight toasted note, vegetal at the back of my tongue, was still there. The mouthfeel wasn’t as dominant, and the aftertaste not quite as pleasant as that with the clay pot. The clay pot definitely mellows out the tea.

Brewed in gray clay vs purple clay teapots from China

Still feeling that these leaves ought to be better, the next day I brewed the leaves in two different clay pots, side by side, using around 3 g leaves, 60 ml water, and 190°F, but beginning with 5-sec brews, increasing a few seconds with subsequent infusions.

Again, a different experience!

The gray clay pot this time gave a sweeter, fruity liquor—finally!

There was honey, there was apricot, there was still a smooth, somewhat buttery mouthfeel. The pot seemed to pull out the best of the leaves. Later infusions brought out some lingering vegetal notes and a touch of astringency, but pleasantly.

That brewed in the purple clay pot, however, retained more astringency, with far fewer sweet notes. Interestingly, when poured into a glass cup, the aroma was similar to that in the Jian Zhan cup, but when poured into a clay teacup that came with the pot, there was almost no aroma. It’s as though the clay completely absorbed the aroma.

I don’t think this pot contributed anything to the tea.

There could be various explanations, from it not being the optimal clay type or clay thickness to the pot being the wrong shape for this tea. Also, I have used this pot only once or twice before today and I don’t know its history, my daughter having purchased it from someone over FaceBook. More frequent use surely will yield better results at some point in the future.

A note—

Having a not-so-great experience with the shiboridashi may have been more a result of not having the optimal amount of leaves, or brewing temp, etc.

An oolong in particular is a complex tea, and you can certainly alter its flavor by how you brew it, manipulating the parameters to get the taste that you prefer. This is one of the fun things about oolongs, and it’s important for people new to tea to keep in mind that there’s not necessarily a “right” way to brew certain teas. If you like what you taste, that’s all that matters!

Verdict on this tea?

So, do I like this tea? When I finally got what I was looking for out of the leaves, a resounding yes.

And when I got vastly different experiences out of the same leaves, also yes, because it’s really a lot of fun to see how the brewing can impact the result; to experience how oolongs are complex and incredible teas, with layers of flavor; and to have a tea that rewards experimentation.

Zerama’s website describes this tea as having an “overwhelming aroma of tropical fruit and honey. The flavor is a perfect blend of fruit and floral with hints of almond. . . . [and a] lingering aromatic finish.”

Although I got what I’d describe as more fruity than floral, I loved the notes that I picked up, and I’m looking forward to discovering what my next experience of this oolong will be!

Sources:

Sources:

–Beurdeley, C., and M. Beurdeley, A Connoisseur’s Guide to Chinese Ceramics, trans. by K. Watson, Harper and Row, NY, 1974.

–Teavivre, “Secrets of Jian Zhan tea cup,” accessed 8/13/20.

–Zhang, X. et al., “Phoenix Dan Cong tea: An oolong tea variety with promising antioxidant and in vitro anticancer activity,” Food and Nutrition Research 62, 2018.

Great content on your blog. Great photos. SLP …

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike

I’m sorry that you had this experience with a Dancong, especially a Ya Shi Xiang. Try it in porcelain with the usual gong fu ceremony, for the first times with short 5 seconds brews and later increasing it. Clay is not recommended for Dancong, because of the taste altering effect that you experienced too.

LikeLike

I did brew it in glass, which is inert like porcelain, but with western brewing. I’ll try it again as you suggest. Thanks for writing!

LikeLike